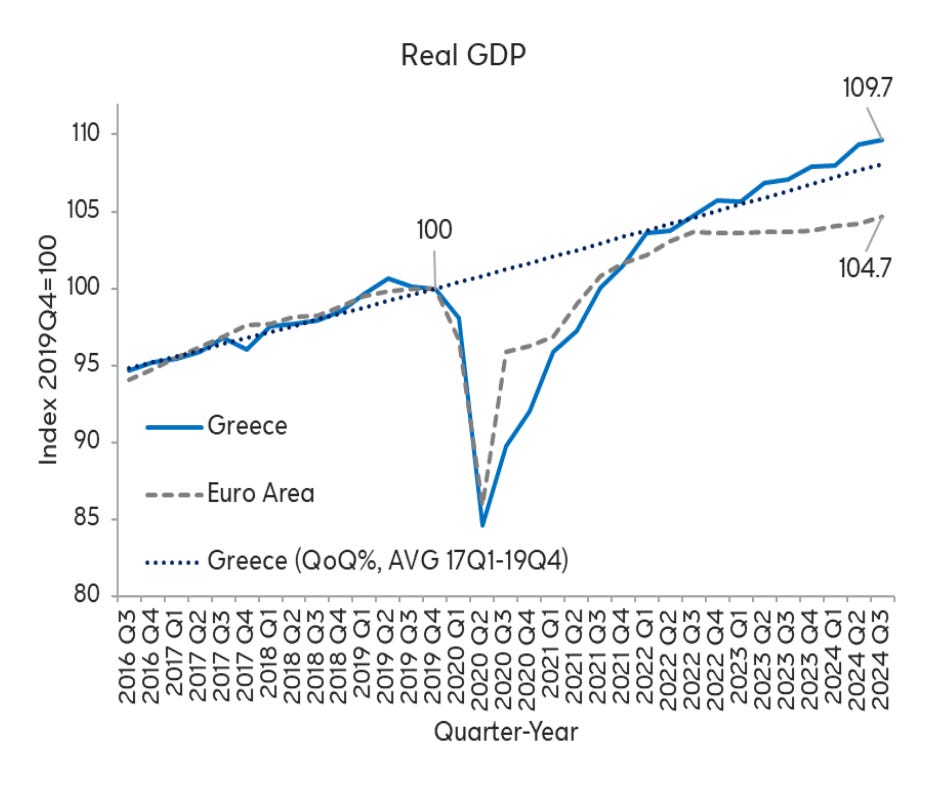

Greece’s recovery story has become a headline cliché in the past year.

Government officials speak of a new era while analysts point to fiscal surpluses and rating upgrades. Tourism numbers keep breaking records.

But not everybody is convinced.

A closer look at the data shows that living standards are stagnant, wages have flatlined, and real economic progress is missing. So what’s the real story here?

How did Greece fall this far?

Greece’s economic problems didn’t start in 2008. They began long before. After the fall of the junta in the 1970s, successive governments relied heavily on borrowing to build roads, expand the public sector, and grow wages.

By the time Greece joined the Eurozone in 2001, its debt had already reached 97% of GDP. And that figure would balloon in the following decade.

Unlike other indebted countries, Greece had no monetary tools left. It couldn’t devalue its currency or print money.

When the global financial crisis hit, credit markets froze. GDP collapsed by over 25% between 2009 and 2014.

Pensions were slashed. Unemployment reached 28%. And public assets were sold off under bailout conditions.

Since then, the country has leaned heavily on tourism and real estate. But these are not engines of productivity. They have not lifted wages or created sustainable growth.

They’ve only hidden the reality that Greece was a country with no clear economic model, no industrial base, and no plan.

Are incomes really growing?

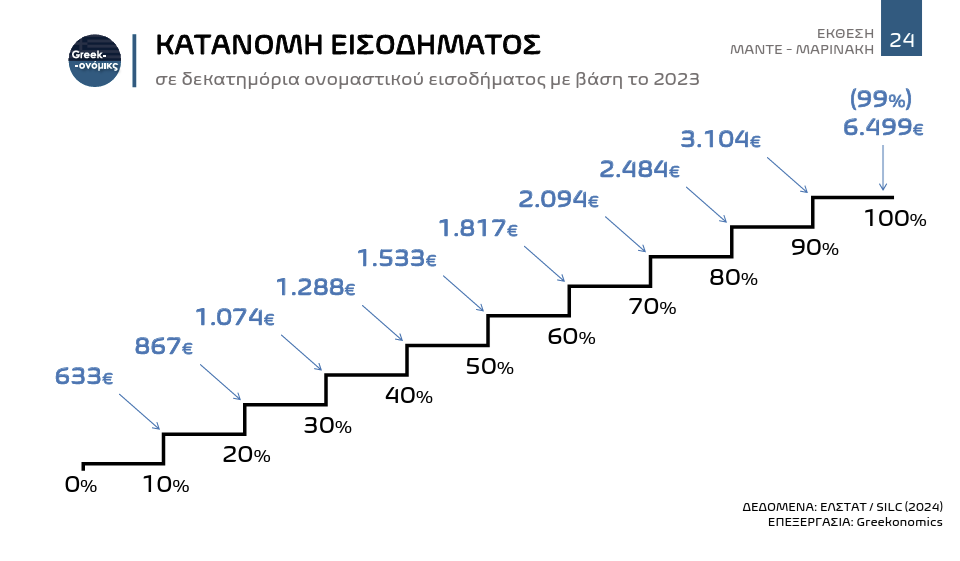

The most common political narrative is that incomes are rising. Technically, that’s true, but only in nominal terms. Adjusted for inflation, the picture changes.

Recent research by Mantes and Marinakis, using data from ELSTAT and Eurostat, sought to uncover the real situation.

According to their research, to be richer than 50 percent of Greeks, you need €1,533 per month. The top 10 percent starts at just €3,100.

These numbers are not competitive by European standards. In France or Germany, that income places you near the bottom.

Under SYRIZA (2015–2019), low-income Greeks saw real income gains, largely due to benefits.

Under New Democracy (2019–2023), gains were concentrated at the top. The poorest 80 percent saw real income growth of less than 1 percent per year.

Meanwhile, the top 10 percent gained the most, especially after 2022, when inflation hit hard and the government failed to cushion the blow.

Even though ND had €8 billion more in fiscal resources per year than SYRIZA, most of it went to debt servicing, defense, and one-off energy subsidies. None of it made a structural difference in real wages.

Is the housing crisis just a price problem?

No. It’s mostly an income problem.

Housing prices in Greece have climbed sharply since 2015. In Athens, the average price per square meter has jumped 88%. But this rise alone does not explain the housing crisis.

Countries like Poland, Hungary, and Romania, where home prices also rose sharply, have seen the burden on households fall.

In Greece, 90% of low-income renters face housing cost stress, according to Mante & Marinakis. That figure is under 30% in the poorest 10 EU countries.

Even middle-class Greeks are affected. Between 2015 and 2023, housing hardship among median-income households dropped across Europe. In Greece, it got stuck at 15%.

This is not due to a lack of housing supply. It’s because incomes have simply not moved.

The government’s handling of Airbnb, the Golden Visa scheme, and bank-held property stock made things worse.

Rent inflation remains out of control while other countries have stabilized. The state misread the problem, and now the housing system is broken.

What happened to real investment?

Greece is still not investing in its future. Most of its capital continues to flow into real estate and public contracts. Industrial investment, the kind that builds capacity and exports, is still flat.

In countries like Slovenia and the Czech Republic, manufacturing investment has lifted productivity and wages. These economies now outperform Greece in both purchasing power and economic complexity.

By contrast, Greece remains stuck at the bottom of the EU in value-added production.

Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity confirms it. Greece produces fewer high-complexity goods than any other EU member.

Even basic processing such as turning cotton into fabric for example, is outsourced. Greece exports raw materials and re-imports finished products at five times the cost.

The root problem is direction and not just capital. Capital flows to housing and defense. Not to technology, logistics, or other competitive industries.

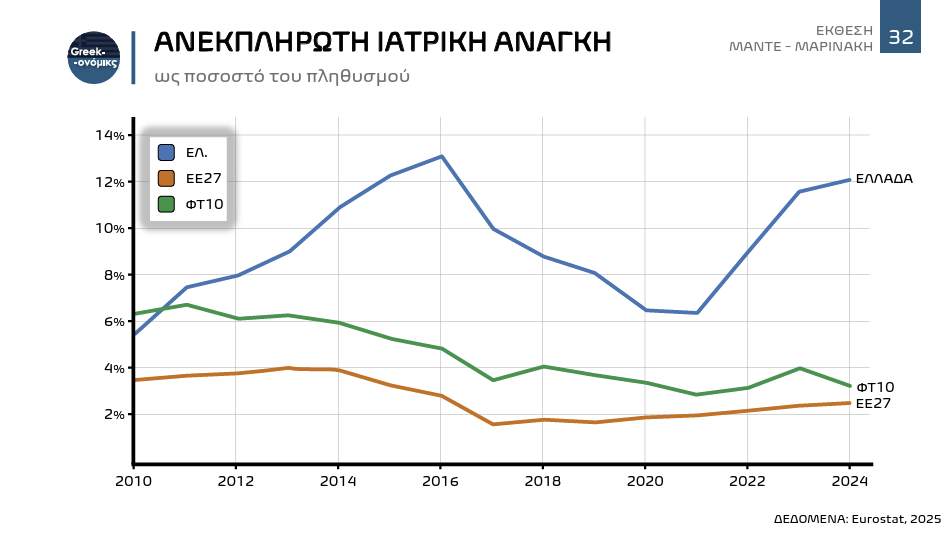

Why is poverty rising in a so-called recovery?

Poverty in Greece is not going away. It’s actually getting worse.

Material and social deprivation remains well above EU averages. Since 2023, it has even increased.

Food prices are high, and the “household basket” scheme had no effect. Energy prices rose earlier and stayed high longer than anywhere else in Europe. Even when subsidies kicked in, the damage was done.

Unmet medical needs have returned to crisis levels. In 2024, 12% of Greeks reported not receiving needed care, five times the EU average.

Crime is also rising again, after falling briefly a decade ago.

These statistics are indicating a system that is not delivering for its people.

Is Greece’s economy moving backwards?

Greece appears to be diverging from Europe. Most European economies have already passed Greece in purchasing power, income, and industrial strength.

Greece is falling behind in every core area that defines long-term prosperity: productivity, income growth, investment direction, public services, and human capital.

The “success story” narrative survives only because the bar is set low and the metrics are selectively framed.

And this is a crisis of choices. Greece had more money, more time, and more support than almost any country in modern history. But it failed to turn those assets into structural reform.

Unless that changes, Greece will not only stay behind, but it might become irrelevant in the European economic landscape.

Bailouts are a thing of the past and now the beautiful mediterranean country is left alone to salvage its economy.

The post Why Greece’s economy is not a success story appeared first on Invezz